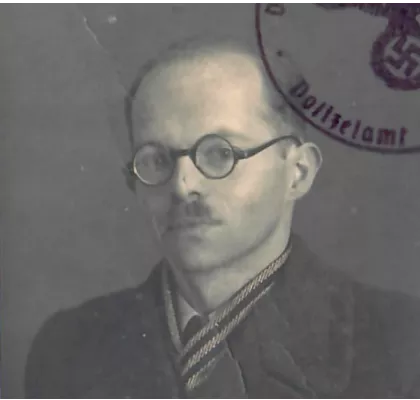

Herbert Kolb (1922-2016)

A Nuremberger in Wulkow

- © Privat

- © Privat

Herbert Kolb was born in Nuremberg on 27 February 1922 as the first of two children to Reta and Bernhard Kolb, who would later go on to become the director of the Jewish community in Nuremberg. Herbert finished primary school in Nuremberg and then attended a secondary school until the forced expulsion of the last Jewish pupils in 1935. After graduating from a commercial school and completing a commercial apprenticeship, he went to Berlin in August 1938 for further training at a private vocational school for fashion, graphics and decoration and to a Jewish art school. In preparation for emigration, he also took courses in carpentry there. When Jews finally lost their last opportunities to gain professional qualifications, he returned to Nuremberg in April 1941 and worked in forced labour in a bookbindery.

After their efforts to emigrate had failed, the whole family was deported to the Theresienstadt ghetto on 18 June 1943. Expecting terrible living conditions, Herbert arrived wearing seven shirts at the same time. In the ghetto, he tried to join the graphics department of the Jewish self-administration. Herbert ended up working as a carpenter and was ordered to join a transport to "Zossen" in August 1944. The Nazis used this code name to disguise the actual destination: Wulkow.

- © Privat

There were 40 people travelling with him, including 17 women. Herbert continued to work as a carpenter in Wulkow. According to him, they had to erect around one hundred buildings, including numerous prefabricated barracks. Herbert wore socks on his hands to protect them against the cold. The prisoners were not issued work gloves. On 31 January 1945, Herbert Kolb was working on the so-called Z construction site, where a new barrack for the NSDAP party chancellery was being built, when he heard explosions. The front was approaching:

„I happened to look back from a small hill [...]. You could just see the road from this one spot in the forest. Normally there wasn't much traffic. But that evening, when I happened to look in that direction, I noticed that the road was clogged with all kinds of vehicles. I saw horse-drawn carriages, cars, lorries and lots of people on foot, on bicycles, with wheelbarrows and other vehicles.“

Herbert Kolb, 2008

The German population was fleeing the approaching Red Army. Herbert and the other Wulkow prisoners discussed arming themselves in this situation, as they feared that the SS might commit a massacre in the camp. On the night of 02 to 03 February 1945, the camp was "evacuated" and the prisoners were forced to walk to Trebnitz railway station. From there began an odyssey across Germany and the occupied "Reich Protectorate". Due to lack of supplies during the eight-day train journey, many prisoners became seriously ill. Herbert was able to help a young fellow prisoner who was suffering from severe gastrointestinal cramps by sharing a dried soup broth cube that his mother had given him in Theresienstadt.

Back in Theresienstadt, the Wulkow prisoners were initially quarantined. He was also reunited with his parents in the ghetto but his sister and brother-in-law had been deported to Auschwitz. In those final months, Herbert continued to work as a carpenter in the ghetto. However, he was sent on another field labour assignment to Regen near Deggendorf for ten days in April. Liberation was near, but first the evacuation transports from camps further east brought half-starved and severely traumatised prisoners to the ghetto. Upon arrival, their first stop was the food at the distribution points. Herbert and his fellow prisoners formed human chains so that the little food they had could be distributed fairly. However, they were powerless against what else the transports had in store for them: the emaciated prisoners brought a typhoid epidemic into the camp. As a result, the survivors were unable to leave the camp immediately after liberation of the ghetto on 08 May. Added to this was the difficulty of finding a means of transport.

„After I left Theresienstadt on 12 June, I travelled to Nuremberg via Karlsbad Eger, partly by bike, partly by train and the last part by car. After staying in Eger for eight days, I arrived on 20 June. After 11 days of negotiations with the military government, I was given three American cars to pick up the former Nurembergers from Theresienstadt. I was back in Theresienstadt on 01 July. We drove back to Nuremberg on the 2nd.“

Herbert Kolb in a letter to his former camp comrade Pavel Weis, 03 July 1946

Not long after, Herbert Kolb set off in search of his sister. He decided to cycle the hundreds of kilometres from Nuremberg to Belsen in the Lüneburg Heath. After four days of travelling, he received the sad news that his sister had died in the Belsen camp two days after giving birth to her child. Herbert and his parents no longer wanted to stay in Nuremberg after everything they had been through. The experiences in Wulkow also continued to torment him. In particular, the abuse at the hands of his fellow prisoner, Kapo Paul Raphaelson.

„And now the most interesting part of my letter to you today. In mid-September I found out that our much-loved 'Rafaelsohn' had become head of the support centre for concentration camp prisoners in some small town in the Rhineland. As you can imagine, I wrote to the military police station there that very same day.“

Herbert Kolb in a letter to his former camp comrade Pavel Weis, 03 July 1946

Paul Raphaelson was subsequently arrested and extradited to Czechoslovakia, where he was sentenced to death in 1947. By this time, the Kolbs had already emigrated to the USA. Herbert initially started working as a carpenter again and later became a successful advertising designer. In his private life, he was an artist, focusing on painting, illustration and calligraphy. In 1950, he married Shoah survivor Laure Wildmann from Philippsburg in Baden. Together they had a daughter, two sons and numerous grandchildren.

In addition to researching the Jewish community of Nuremberg, Herbert Kolb also gathered extensive knowledge about Wulkow and was a central figure in the networking of the Wulkow survivors. His many drawings and sketches from the Wulkow camp made a significant contribution to the remembrance work of the Wulkowers.

Herbert died in 2016.