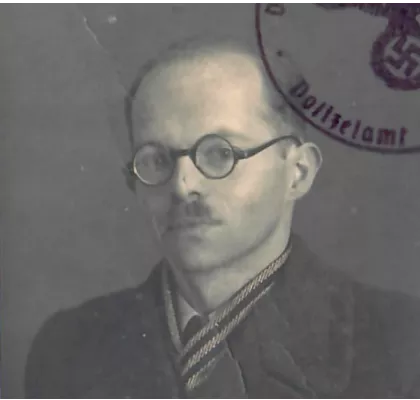

Klaus Scheurenberg (1925-1990)

„I want to live“

- © WDR

- © WDR

Born on 20 September 1925 to Jewish couple Paul and Lucie Scheurenberg in Berlin-Charlottenburg, Klaus Scheurenberg spent the first two years of his life in Letschin (Oderbruch).

In 1927, the family moved back to Berlin, where Paul and Lucie ran a fruit business. Frida - a neighbour from Letschin who moved to Berlin with them - took care of their home and the children. Klaus Scheurenberg started school in 1931 and initially did not attend religion classes. He later received Jewish religious education with a few other children. In these lessons, he learnt about Jewish history for the first time, studied Hebrew from the second year and attended the synagogue.

In 1933, anti-Semitism continued to rise and even friends of the Scheurenberg family began to turn their backs on them. Nevertheless, Klaus joined the Hitler Youth on one of the social evenings, only to be thrown out again at the next meeting. Klaus continued to go to school and became closer friends with other Jewish boys. At the beginning of 1936 - three years before the end of tenant protection for Jews - the Scheurenbergs were given notice to leave their flat in Berlin-Reinickendorf. The parents were allocated a two-room flat in Berlin-Mitte. Paul soon became the building's caretaker.

It was also in this year that Klaus Scheurenberg began to attend the Jewish school and from 1937, the Jewish secondary school because it was closer to his home. In 1937, at the age of 12, he was sent to Schönlake in West Prussia by a Jewish organisation. It was his first group trip and also where he met his friend Max Ottinger (Mucki).

In September 1938, on the Sabbath after his 13th birthday, Klaus celebrated his bar mitzvah in the Jewish community and received his Hebrew name Akiva Ben Shaul (i.e. Akiva, son of Shaul, his father's Hebrew name). He had saved money for this particular day by working as a ball boy on the tennis court. He wanted to make it unforgettable. With the November pogroms of 1938, life changed abruptly for Jewish families. This was also the case for the Scheurenbergs. Klaus' brother Heinz emigrated to Palestine, while the rest of the family remained in Berlin.

Klaus went to school in the mornings and to Aliya preparation in the afternoons, where he gained a great deal of knowledge and, together with Mucki, consistently followed this path. In August 1939, he spent four weeks in Rüdnitz at a preparatory camp for emigration. During this time, he had already become the head of his community's cultural work division.

The 1st of September 1939 was his penultimate day in Rüdnitz and - with the German invasion of Poland - the beginning of the Second World War. It was his last chance to emigrate to Palestine. However, on his father's orders, Klaus Scheurenberg did not take this opportunity. In 1940, he attended the Hakhshara, a Jewish preparatory camp with a focus on agriculture. The camp educated its participants according to the principles of a kibbutz by emulating life in the communal settlement in Palestine. In the spring of 1940, he and his friend Mucki went to Schniebinchen in Lower Lusatia, where he was to become a farmer and Zionist.

In 1941, Klaus Scheurenberg began his apprenticeship as a carpenter, which lasted only for four months. He then began working for the Dr Otto Kolshorn company in Niederschönhausen. The company waterproofed sleepers and produced wood-block paving.

As of 19 September 1941, Klaus Scheurenberg, like all Jews, was forced to wear the yellow star. In 1942, he and his mother were picked up from their Berlin flat by the Gestapo for the first time and taken to the detention centre in Große Hamburger Straße. After only a few hours, his father was able to bring them home again as he knew people working at the Gestapo from his job as a caretaker. The family also managed to avoid a second eviction.

- © Centrum Judaicum, Berlin

In this year, Klaus Scheurenberg was summoned to the pre-draft physical examination. He even received a military service pass and a pass for the Reich Labour Service, but with the stamp "Unworthy of military service - Jew".

When the Gestapo evacuated Elsässer Strasse in Berlin on 27 February 1943, Klaus escaped deportation once again as he was not at home. A short time later, he met Helga, a non-Jewish German woman, and spent a few weeks with her. They went swimming, rowing or even to the cinema together as he had learnt to effectively hide the yellow star. During this time, Klaus worked for the city railroad company.

When he came home on 07 May 1943 after an afternoon with Helga, he saw the Gestapo outside the house. The family was picked up and taken back to the detention centre in Große Hamburger Straße. The next day they were registered for Theresienstadt. Ten days later, on 17 May 1943 and "after a cup of malt coffee and a jam sandwich", they were deported to Theresienstadt, where the train arrived late in the evening.

There, Klaus Scheurenberg was initially assigned to the corpse carrier detachment but after two days he moved to the carpentry workshop. He worked for 70 hours a week. In April 1944, Klaus was enlisted to build barracks in the Wulkow satellite camp. He continued to work as a carpenter there. Despite the difficult conditions - constant hunger, cold, punishments - he survived both Wulkow, and on 11 February 1945 the eight-day trip back to Theresienstadt, where he saw his parents again and was sent to work in a bakery.

On 08 May 1945, the Red Army liberated the Theresienstadt ghetto. All prisoners tried to make their way back to their homes. At the end of June 1945, Klaus returned to Berlin on a lorry, where he moved into a small flat.

From 1947 onwards, the former Wulkow prisoners met on a regular basis. Klaus Scheurenberg arranged a meeting in Berlin in 1984, during which the WDR film team shot footage for the documentary "Gesucht wird...".

In 1981, he became one of the chairmen of the Society for Christian-Jewish Cooperation in Berlin (GCJZ). He recorded his biography in his first book "Ich will leben" ("I want to live"), which was published in 1982. Eight years later, in 1990, his second book "Überleben. Flucht- und andere Geschichten aus der Verfolgungszeit des Naziregimes" ("Surviving. Tales of escape and other stories during the period of Nazi persecution.") came out.

Klaus Scheurenberg died in Berlin on 09 June 1990. He was not yet 65 years old.