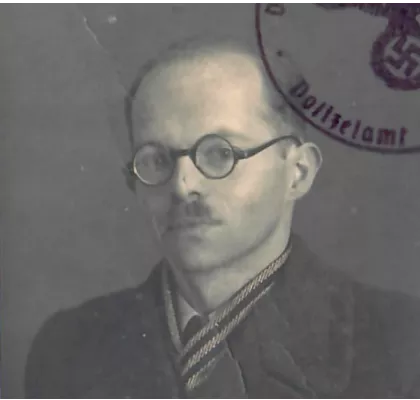

Ervin Kosiner (1900 – 1972)

Wulkow's civil engineer

- © United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Collection. From the Centropa Archive

Ervin Kosiner was the chief engineer in charge of building the barracks in Wulkow.

Born on 16 June 1900 in Bukol, 30 kilometres north of Prague, Ervin Kosiner grew up as one of eight children in a Jewish family with no religious education. Instead, like many Jewish families in Bohemia at the beginning of the 20th century, the family celebrated the Christian holidays of Easter and Christmas.

In an interview in 2005, his daughter Milena Procházková remembered him as a "great joker" with a "penchant for humour": at the age of seventeen, he was conscripted into the artillery division during the First World War, but later did not tell his daughter much more than "that he constantly had a pain in his bum" because the artillerymen pulled the guns with horses and he was therefore constantly in the saddle.

After the First World War, Ervin studied civil engineering in Czechoslovakia at the Czech Technical University in Prague and later worked as a civil engineer. In 1928, he married Hedvika Sternová, nine years his junior, in Prague. Their daughter Milena was born in 1930. The young family led a happy life in Prague between the wars: Kosiner was a sought-after civil engineer in economically booming Czechoslovakia. He earned good money, and in the summer he and his siblings' families went on holiday together to Yugoslavia.

However, this all changed with the collapse of Czechoslovakia and the invasion of the Wehrmacht in the spring of 1939 when the Kosiners had to vacate their flat in Prague's popular Letna district and move to another neighbourhood. It was no longer possible for Ervin Kosiner to flee abroad, as some of his siblings had done in the 1930s. As "Jews" - third-class citizens in German-occupied Prague - the Kosiners only received ration stamps for bread, flour and potatoes. It was only thanks to the support of friends that they survived the war years in Prague without going hungry. In September 1943, Ervin, Hedvika and Milena Kosiner were deported to the Theresienstadt ghetto.

All three had to work in Theresienstadt: Hedvika in the "cleaning crew" and later in the bakery, Milena in a factory. Ervin was also in demand as a civil engineer in Theresienstadt and, after a few months, volunteered to work in the "Zossen Barrack Construction". He arrived in the forest near Wulkow with one of the first transports at the beginning of March 1944. As an experienced civil engineer, he was put in charge of the construction site.

Kosiner was responsible for the construction of the barrack settlement. He answered to SS commandant Franz Stuschka. He was assisted by subordinate engineers. The construction site was constantly expanded and with it, his responsibility grew. Stuschka held Kosiner personally responsible for all defects and even attacked him physically. Due to this pressure, Kosiner demanded strict discipline from his workers.

Some of the postcards that Ervin Kosiner sent from Wulkow to his wife Hedvika and his then fourteen-year-old daughter Milena have survived until today. They contain almost no information about everyday life in the camp in Wulkow as all mail was censored. However, the correspondence shows how important it was to reassure each other of one's own well-being in order to ease the other's worries. Just a few days after his arrival, Ervin wrote: "I am doing very well, we are living in barracks in the forest, it is warm, the food is excellent. [...] Don't worry about me." And a month later: "Dearest Hedo and Milenko! [...] I'm happy that you're doing well. So am I, but so much to do. [...] Don't worry, I'm healthy and looking good."

It took almost one year and an eight-day return journey on the train to Theresienstadt for Ervin Kosiner to be able to briefly meet his family again. Another assignment followed: at the end of March 1945, Ervin sent a postcard with "1000 kisses and hand-kisses" to his wife in the ghetto, with the return address "Construction manager, field labour group".

After the end of the war, the Kosiners returned to Prague and, after some waiting, also got their flat in Letna back. Of the many Jewish families who had lived in the house before the war, they were the only ones to return. They had also lost all their household possessions. There was no compensation, quite the opposite: the furniture left behind in the flat by the German residents now belonged to the state and had to be purchased by the Kosiners. The family had escaped with their lives, but it was all they had. At the age of 45, Ervin Kosiner had to start all over again. He reopened the planning office that he had run before the war.

Ervin Kosiner's experiences in Wulkow continued to haunt him after 1945. Many of the Czech Wulkowers came to Prague after the war and kept in touch with each other for decades. Kosiner himself organised the first major meeting in 1947 in a restaurant in Prague called "U Sojku". The reason for this meeting was his desire for a discussion after a prisoner who had suffered corporal punishment accused Kosiner of abusing his position in the camp.

In the same year, Ervin Kosiner received a letter from Franz Stuschka, the former camp commandant of Wulkow, who was in American custody in Salzburg at the time. In the letter, Stuschka asked the "honoured engineer [...] from a competent authority for a certificate of good conduct regarding my activities in Wulkow" in order to obtain a release from prison. Stuschka listed a series of alleged charitable activities available for the prisoners, some of which he had made possible "contrary to orders received": "Mail and parcel transport, additional procurement of medication, food bonuses, dental treatment [sic!], the difficult return journey by train contrary to orders to walk, etc."

He also talked about the violence in the camp. In his letter to Kosiner, Stuschka, who was remembered in all prisoner reports as a brutal tyrant, presented himself as a person responsible for discipline in the camp who endeavoured to achieve justice. He emphasised two arguments: there had been no "baseless disciplinary measures" and he had intervened when prisoners were beaten by guards. A perfidious formulation of Stuschka's camp policy, which granted only him, the camp commandant, the authority to interpret punishable offences and the unlimited monopoly on the brutal, sadistic and degrading violence against the prisoners. It is unknown whether Kosiner ever replied to the letter.

Ervin Kosiner only ran his planning office until the early 1950s, as freelance construction planners were not sought after in the now communist-ruled ČSR. Kosiner was hired as the chief engineer at the state-run CHEMOPROJEKT, where he implemented several major construction projects. He remained in this position until his death in 1972.

Ervin Kosiner died of a heart attack. It was his fourth; he had suffered the first two in Wulkow.

Read more:

Interview with Ervin Kosiner's daughter Milena Procházková from 2005 and additional images (languages: English, Czech)