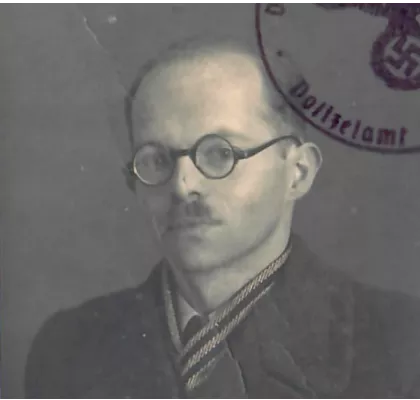

Ingeborg Kantor (1924-2016)

The helpful optimist

- © USC Shoah Foundation

Ingeborg Kantor was born as Ingeborg Nattmann on 29 May 1924 in Berlin. Her father was Arthur Nattmann, a non-Jewish German who emigrated to the USA in 1929 after his divorce. Ingeborg's mother, Erna Nattmann née Israel, was Jewish. Ingeborg lived on Kantstraße in Berlin-Charlottenburg with her mother and her maternal grandparents. In a video interview with the USC Shoah Foundation in 1997, Ingeborg said that the family had been very poor and not very strictly religious. However, she regularly went to the "Friedenstempel" synagogue in Berlin with her grandfather on Friday evenings. Jewish holidays were also celebrated in the family.

Ingeborg started going to school from the age of five and, thanks to her high performance, was later even allowed to transfer to a school where she received specific support and additional lessons. Shortly after the November pogroms in 1938, state schools became inaccessible to Jews. This meant that Ingeborg also had to abandon her education.

She and her mother were given opportunity to leave Germany and emigrate to England. However, due to her grandparents and her grandfather's cancer, they decided not to leave and stayed in Berlin. Ingeborg's grandparents were deported in October 1942. First to the Große Hamburger Straße detention centre and then to the Theresienstadt ghetto.

As Ingeborg could no longer attend school and was dependent on food stamps, she decided to find a job. She worked as a waitress in a Jewish café for a year before working as a temp in an office until the start of the war. She was then sent to the Siemens assembly line by the employment agency. The "Fabrikaktion" on 27 February 1943 also meant the end of Ingeborg's job at Siemens. Together with her colleagues, she was taken to the detention centre in Berlin's Rosenstraße, where she also met her uncle. Ingeborg stayed at the centre until the "Rosenstraße protest", which her aunt also participated in.

On the day of the "Fabrikaktion", Ingeborg's mother had been advised by her boss to leave the company early and go home. The two met up again in their shared flat.

In order to continue to support herself, Ingeborg needed to find another job. The employment agency sent her to Szczecin railway station, where she cleaned trains.

When she came home from work one day, the Gestapo were already in her flat. Ingeborg and her mother were deported to Theresienstadt.

She said that at first she was happy to see her grandparents again and that she no longer had to fear the bombs. However, she did not know what fate was awaiting her. A few days after her arrival, she learnt that her grandparents had died shortly after being deported to Theresienstadt.

In Theresienstadt, Ingeborg worked in the so-called "delousing" office. She used the little free time she had there to participate in the performance of the operetta "Die Fledermaus".

Ingeborg received parcels from her aunt containing - among other things - potatoes, bread and lipsticks.

„We were allowed to write postcards, but we couldn't tell her what we really wanted or what we needed. So I wrote a postcard, her name is Israel, Mrs Charlotta Israel - and I wrote the name of our bakery on it. She understood. She sent us bread. She was very clever. And so I carried on. I wrote her a card, née Ellermann. That was the greengrocer round the corner. So she sent us potatoes. And then I got even smarter and sent her a card: Mrs Charlotta Israel, née Scherk. Scherk was a cosmetics company. [...] She sent lipsticks. She could get the lipsticks very easily. And I got a big loaf of bread for it. I could trade.“

Ingeborg was sent to the prison in Theresienstadt for redeeming a food stamp she had found on the ground. As the stamps bore unique numbers, and Ingeborg did not change them, her "deception" was noticed when the food was being served. Many of the people who were in prison in Theresienstadt at the time were subsequently deported to Wulkow. Unlike other prisoners, they did not volunteer but were sent to Wulkow as a form of punishment. Ingeborg's boss in the "delousing" office promised to get her out of this transport. However, as Wulkow was near Berlin, she decided to go after all.

After saying goodbye to her mother in August 1944, she was deported to Wulkow together with 20 other women, including her friend Traute Schumann.

In Wulkow, Ingeborg had a variety of different jobs. For the most part, these were pointless and were purely intended to keep the prisoners busy. For example, she had to pick up pine needles from the ground and collect them in large sacks. At one point, she worked the tar oven and was glad that at least she no longer had to freeze while she worked. She shared food and clothes with her friend Traute Schumann in Wulkow.

On the night of 02 to 03 February 1945, all prisoners of the Wulkow satellite camp were made to walk to the railway station in Trebnitz, from where they were deported back to Theresienstadt over the course of eight days. Once back in Theresienstadt, Ingeborg was first quarantined and then finally able to see her mother again. As long as Ingeborg was in Wulkow, her mother remained in Theresienstadt and was not deported.

Ingeborg began to work in the kitchen serving food. In the kitchen, she found out that the Red Army was in Theresienstadt. She stayed in Theresienstadt to provide assistance until July 1945, two months after the liberation.

She eventually returned to Berlin with her mother, where they lived with Ingeborg's aunt and uncle for a while. They were later able to move back into their old flat in Charlottenburg. However, they did not want to stay in Berlin and decided to emigrate to the USA. They arrived by ship in Brooklyn on 14 March 1947. After initially staying in a hotel on Broadway, they were later able to move into an own flat on Westend Avenue.

One day, while walking along Broadway, Ingeborg met Alfred Kantor, her future husband. Alfred Kantor had survived the Auschwitz extermination camp and the death march from Schwarzheiden to Theresienstadt. Ingeborg and Alfred had already seen each other on the ship to America, but had not gotten to know each other. Alfred worked as a freelance artist. The couple got married on 28 July 1950.

Their son Jerry was born on 04 March 1948, their daughter Monica on 29 March 1955. The family stayed in New York until they bought a house in Fresh Meadows, where they lived until 1980.

When Monica took a job as a music teacher in Maine, Ingeborg and Alfred Kantor also moved there.

Ingeborg died in Boston in 2016 at the age of 91.