Investigations and trials

The camp commandant Franz Stuschka was put on trial before the Vienna People's Court in late 1949. Despite the countless instances of abuse, he was given only a relatively light sentence. Two years earlier, former prisoner and Kapo Paul Raphaelson stood trial before a Czechoslovakian court. The conditions of his trial and the punishment were much harsher: he was sentenced to death.

After liberation, Paul Raphaelson returned to his home town of Mönchengladbach, where he founded a support centre for former concentration camp prisoners and became actively involved in the Jewish community. His former fellow prisoners approached the British occupation authorities and demanded Raphaelson be held accountable for his acts of violence in Wulkow. They presumably had not expected that he would subsequently be sentenced to death by a Czechoslovakian court. Survivors also played a key role in the prosecution of Franz Stuschka.

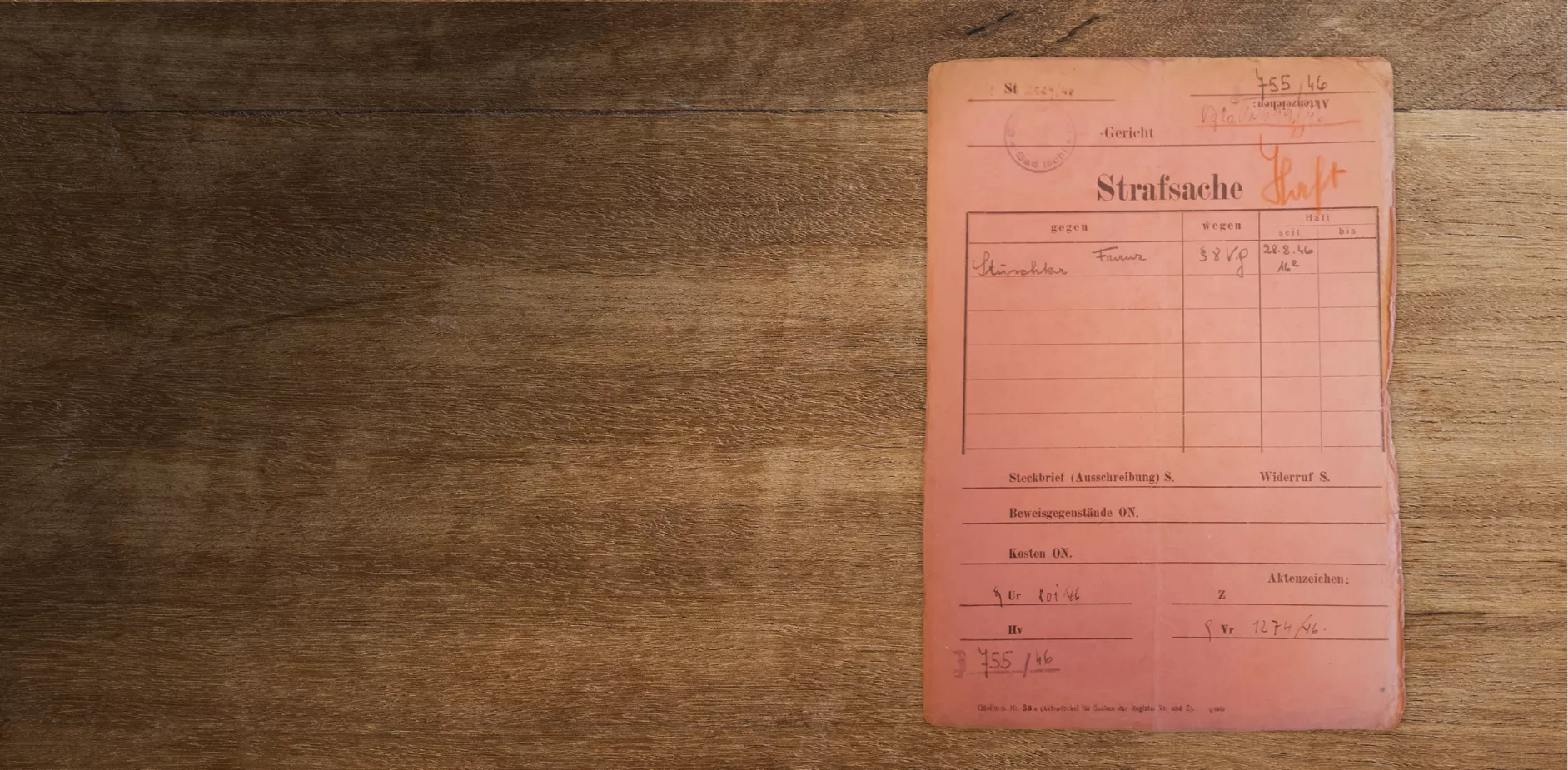

- © CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 DEED, Quelle: WStLA

- © CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 DEED, Quelle: WStLA

Albert Jungmann, who by then was working for the Vienna criminal investigation department, interrogated him and took numerous witness statements from his former fellow prisoners. On 15 December 1949, the main trial began at the Vienna People's Court. Two days later, the verdict was pronounced: seven years of hard labour imprisonment for treason, abuse and violation of human dignity. The deportations from Wulkow that resulted in prisoners' deaths, for which he was also responsible, were not addressed in the trial. The judge also did not recognise the type of camp Wulkow had been nor did he acknowledge Stuschka's actions as commandant. Initially on probation, Stuschka was already released in early 1951 as his pre-trial detention was credited to his sentence.

„If one were to take the view that every construction site on which concentration camp prisoners were used, and who also slept on the construction site, constituted a separate concentration camp, one would end up with a vast number of practically untraceable concentration camps.“

From the guilty verdict of the Vienna trial, 1949

While the survivors of the Wulkow camp told the court about the numerous acts of violence committed by Stuschka, the accused himself claimed to be innocent. On the contrary: he went so far as to cynically suggest that the prisoners had been "lazy" and "cheeky". His defence strategy was also to purport that Wulkow was not a concentration camp and that he was therefore not a commandant, but merely a construction supervisor. In a letter to the actual construction supervisor, former prisoner Ervin Kosiner in Prague, he even asked for a positive "certificate of good conduct". When a German television team tracked him down in Vienna in 1985, he considered himself as the "true victim": Eichmann and his superiors had "trampled all over him" because he had been too "soft".

„What a mockery - at the same time I was interrogated and accused of inhumanely housing prisoners and feeding them badly! They had more for breakfast than I had all day. How happy I would be if I was treated the same way today that I treated the prisoners.“

Letter from Stuschka to a Gisela, 1948

In early 1963, foreign public prosecutors' offices began to criticise the state of Berlin for the slow pace at which Nazi crimes were being prosecuted. As a result, a "RSHA working group" was formed, consisting of up to 12 public prosecutors. They investigated former members of the RSHA who, from their desks, had prepared and drafted orders to commit murder. Franz Stuschka and his deputy Richard Hartenberger were investigated in the matter of the "Final Solution to the Jewish Question". They were accused of "involvement in the murder of Jews in concentration camps through the imposition of protective custody". Again, the accusation did not relate to Wulkow, but to the actions of both men in the "Jewish Department". It was not possible to prove that they had imposed protective custody.

In the RSHA proceedings, numerous employees of the alternative site were also investigated. The desk offenders were accused of being guilty of accessory to murder. According to an amendment to criminal law in 1968, the prosecution would have been required to prove base motives or that the offences had been committed in a cruel and insidious manner. As this was virtually impossible and all but four cases were dropped.

„There is no reliable evidence that the term 'return undesirable' did not only mean that the prisoners were not to be returned to the Wulkow camp, but also that it contained an order or recommendation to kill them.“

From the closing statement of 6 February 1979

In 1969, the Central Office of the State Justice Administrations for the Investigation of National Socialist Crimes was erroneously sent statements about Wulkow in the course of investigations into the Trebnitz satellite camp. This led to renewed investigations into Stuschka. This time, the deportations from Wulkow were the explicit subject of the investigation. Ten years (!) later, they were dropped. Stuschka was never held accountable for the deportations from Wulkow.